Neurontin (gabapentin) and the newer Lyrica (pregabalin) are two anticonvulsant and analgesic medications originally prescribed for the treatment of epilepsy. Neurontin was originally licensed in the United States and Canada in December 1993 for use as an adjuvant medication to treat seizures and epilepsy. Lyrica on the other hand, is a much newer drug that received approval for use in the treatment of epilepsy, diabetic neuropathic pain, and post-herpetic neuralgia in 2005, and is considered as a much more powerful version of gabapentin itself. In June 2007, Lyrica was also approved as a treatment for fibromyalgia. The mechanism of action of these two drugs is still partially unknown to medical science, but they’re though to be able to reduce the production of some neurotransmitters in the brain that are deemed responsible for pain and convulsions.

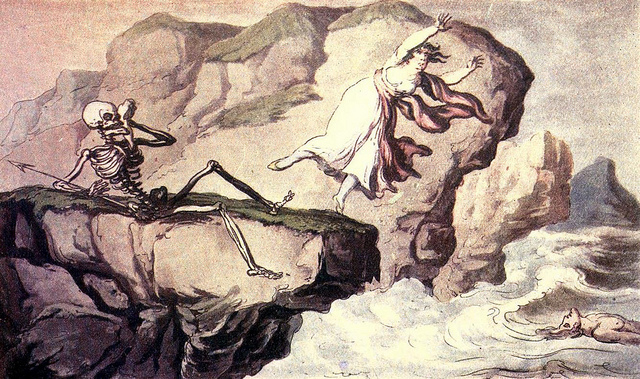

The Suicide – Photo by: Arallyn! – Source: Flickr Creative Commons

Gabapentin and Pregabalin – a marketing fraud that is now part of American history

In 1998 after a few clinical trials suggested that Neurontin could be moderately effective to treat diabetic neuropathic pain and post-herpetic neuralgia, the drug saw an explosion of unapproved off-label prescriptions to treat all kinds of pain, including migraine [1, 2]. Both Lyrica and Neurontin could be effectively used to suppress the symptoms of several painful nerve conditions, but not to treat them, so doctors started to overprescribe them, pushed by the pharmaceutical companies that saw a new potential revenue. In 1998 Parke-Davis, the original manufacturer of gabapentin, launched a marketing program that would push the positive reviews of this otherwise unsuccessful medication using the media power of the so-called “Key Opinion Leaders” (KOL) [3]. Thanks to the massive illegal promotion of its off-label uses (which included even bipolar disorders), in just a few years the US sales of Neurontin were boosted from the initial $98 million/year to an amazing $2.7 billion. However other systematical studies published later helped assess the real effectiveness of Neurontin for this specific conditions, reporting that just a minority of the patients (23%) actually received any benefit from the treatment with this drug [4, 5].

Neurontin and Lyrica are now owned by Pfizer, who had to pay $430 million in 2004 to settle criminal and civil liability due to its illegal off-label promotion of the first drug (which were estimated to account for about 90% of total sales of this drug) [6]. A few years later, in 2009, Pfizer had to pay again $2.3 billion for the illegal promotion of four other drugs, including Lyrica [7]. Why they kept doing if they were punished for that the first time around? As steep as these payments could seem, it’s quite obvious that they just represents nothing more than a fraction of what the same pharmaceutical company makes in a single year of illegally marketing a single one of these drug for off-label uses.

Dangers and side effects of Neurontin (Gabapentin) and Lyrica (Pregabalin)

The main issue about the off-label marketing of these two drugs, is that neither of one is devoid of serious side effects. The dangers associated with the use of Neurontin and Lyrica are quite significant instead, and may even pose patient’s lives at risk. According to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), these antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) do in fact “increase the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior in patients taking these drugs for any indication. Patients treated with any AED for any indication should be monitored for the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidal thoughts or behavior, and/or any unusual changes in mood or behavior [8]”. Subsequent researches confirmed a strict association between suicidal behaviors and use of gabapentin and pregabalin, which can be even more dangerous as an overdose of this drug can prove to be fatal, especially if combined with alcohol in case of intentional ingestion [9].

Another serious side effect of the antiepileptic drugs is the one found by the researchers of the Stanford University School of Medicine in a recent study. AED may in fact may prevent the formation of new brain synapses, reducing the so-called “brain plasticity” [10]. Although adult brains do form much less new synapses than a children or adolescent’s brain, these medication still dangerously reduce the potential for the self-rejuvenating activities of the brain. While epilepsy can be associated with an excessive numbers of synaptic connections in specifically vulnerable areas of the brain, the medication cannot distinguish between “good” and “bad” new synapses, especially when used to treat other conditions such as neuropathic or post-herpetic pain. Brain plasticity is also a continuous mechanism that prevents all age-related cognitive decline, meaning that a drug that directly reduce this natural neural activity will cause a faster brain decline [11].

REFERENCES

- Backonja M.. Beydoun A, Edwards KR et al. Gabapentin for the symptomatic treatment of painful neuropathy in patients with diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998; 280(21): 1831-6. http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/280/21/1831

- Rowbotham M, Harden N, Stacey B et al. Gabapentin for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998; 280: 1837-42. http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/280/21/1837

- Steinman MA, Bero LA, Chren MM, Landefeld CS. Narrative review: the promotion of gabapentin: an analysis of internal industry documents. Ann Intern Med 2006; 145:284-293. http://www.annals.org/content/145/4/284.full

- Backonja M.. Beydoun A, Edwards KR et al. Gabapentin for the symptomatic treatment of painful neuropathy in patients with diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998; 280(21): 1831-6. http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/280/21/1831

- Rowbotham M, Harden N, Stacey B et al. Gabapentin for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998; 280: 1837-42. http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/280/21/1837

- Tansey, Bernadette (2004-05-14). “Huge penalty in drug fraud, Pfizer settles felony case in Neurontin off-label promotion”. San Francisco Chronicle. p. C-1.

- USAtoday30.usatoday.com. “Pfizer fined $2.3 billion for illegal marketing in off-label drug case – USATODAY.com”. http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/money/industries/health/2009-09-02-pfizer-fine_N.htm Retrieved 2015-10-14.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “Drug Safety Labeling Changes – Lyrica (pregabalin) Capsules”. www.fda.gov. Retrieved 2015-10-14.

- Patorno E, Bohn RL, Wahl PM, et al. (April 2010). “Anticonvulsant medications and the risk of suicide, attempted suicide, or violent death”. JAMA 303 (14): 1401–9. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.410. PMID 20388896.

- Çagla Eroglu, Nicola J. Allen, Michael W. Susman, Nancy A. O’Rourke, Chan Young Park, Engin Özkan, Chandrani Chakraborty, Sara B. Mulinyawe, Douglas S. Annis, Andrew D. Huberman, Eric M. Green, Jack Lawler, Ricardo Dolmetsch, K. Christopher Garcia, Stephen. “Neurontin and Lyrica are Highly Toxic to New Brain Synapses Cell.”

- Mahncke, Henry W.; Bronstone, Amy; Merzenich, Michael M. (2006-01-01). “Brain plasticity and functional losses in the aged: scientific bases for a novel intervention”. Progress in Brain Research 157: 81–109. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(06)57006-2. ISSN 0079-6123. PMID 17046669.

Be the first to comment on "Neurontin and Lyrica – two treatments for pain that can lead to suicidal thoughts"