Inferior vena cava filters (IVC filters) are metal medical devices implanted inside the inferior vena cava to trap blood clots and prevent them from reaching the lungs, where they can cause a life-threatening pulmonary embolism (PEs). To be safely implanted, this device, which acts like a metal cage that would trap the blood clot, needs to be surgically applied by a specialist [1]. The inferior vena cava is one of the largest blood vessels in the human body, whose function is to carry deoxygenated blood from the lower limbs, up to the heart and then the lungs. When a blood clot is formed in the legs, arms or hips, it could travel through the inferior cava up to the lungs, creating a blockage called pulmonary embolism that could threaten a patient’s life. To avoid blood clots from forming, the standard treatment is usually a preventive therapy with anticoagulants such as warfarin, heparins or the newer Novel Oral Anticoagulants (NOACs) [2]. However, some patients cannot tolerate this therapy because they are at a high risk for bleeding, in which case the only available option is being implanted with this device. Depending on the duration of the placement some IVC filters are permanent, while others are temporary or retrievable. Permanent filters are usually inserted in those patients who keep suffering from deep venous thrombosis (DVT) even if they’re under anticoagulant therapy.

IVC filters complications and dangers

However, these surgical implements are not devoid of dangerous complications. In August 2010, the FDA released a safety alert announcement about the risk and adverse events associated with the use of an IVC filter During the period between 2005 and 2010, 921 total reports of adverse reactions were identified. Of these 328 consisted of device migration, 146 of embolizations after detachment of device components, 70 of perforation of the inferior vena cava, and 56 involved filter fracture. The FDA reported that most retrievable filters that should only be used for short-term placement were kept inside patients’ bodies for a much longer time. In 2014 the FDA updated recommendation explained that retrievable devices should be removed between the 29th and 54th day after implantation in patients in which PE subsided [3]. The data published from a 2013 study from the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) showed that up to 18.3% of retrieval attempts were unsuccessful. Also, 7.8% of patients who were implanted with this device suffered from venous thrombotic events, including 25 pulmonary emboli, even while the filter was already in place. This same study, which was performed on a total of 952 patients, concluded that “the use of IVC filters for prophylaxis and treatment of venous thrombotic events, combined with a low retrieval rate and inconsistent use of anticoagulant therapy, results in suboptimal outcomes due to high rates of venous thromboembolism” [4].

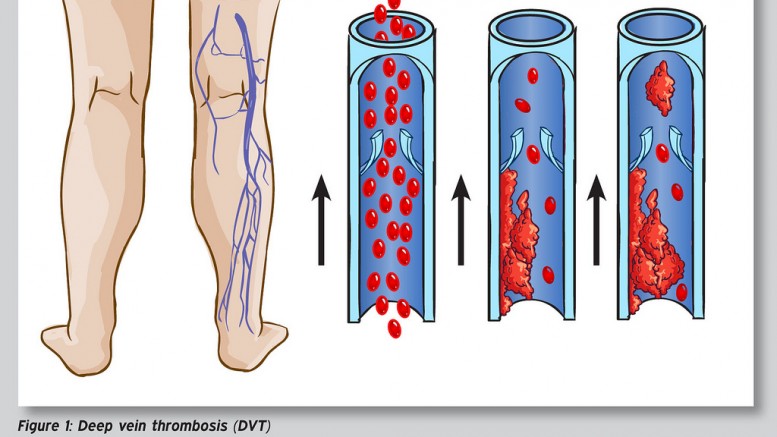

Deep Vein Thrombosis – Photo by: sportEX dynamics 2012;31(January):18-22 – Source: Flickr Creative Commons

Inferior vena cava filters lawsuits consolidated in Multi-District Litigations

About 200,000 filters are implanted every year to prevent PE, with a market of up to $435 million in 2015. Symptoms of a blood clot may include faster heartbeats, abdominal and back pain, flushing, sudden nausea, and vomiting. Because of the serious complications associated with these surgical implements, several lawsuits have been filed against the manufacturers, including Cook Medical (Gunther Tulip and Celect) and C.R. Bard (Recovery, G2, and G2 Express). A study published in 2010 showed that 25% percent of the devices manufactured by Bard fractured and embolized, causing life-threatening symptoms to patients and even a sudden home death [5]. A later, larger scale study published in 2012, showed that the Bard Recovery were associated with an alarming 5.5-year fracture risk of 40% [6].

In the various litigations, the plaintiff accuses the manufacturers companies and their subsidiaries of negligence, design and manufacturing defects, negligent misrepresentation, failure to warn and breach of implied warranty. Since the first IVC filter lawsuits were filed in 2012 against Bard in California and Pennsylvania state courts, the number of litigations against the manufacturing companies kept growing. In July 2015, more than 100 litigations were filed from 11 different districts, so litigation has been consolidated under Judge Richard L. Young under Multi-District Litigation (MDL) 2570 in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Indiana. In August 2015, the U.S. Judicial Panel on MDL consolidated 22 lawsuits against Bard to the U.S. District Court District of Arizona. In February 2015, C.R. Bard settled the case of Kevin Philips, a patient who suffered from a heart perforation after the Recovery filter broke inside his body. Just 10 days after the trial began, the company settled with the plaintiff for an undisclosed sum of money.

Defendants argue that they cannot be deemed responsible for the damage caused to patients, as the end users of their products are the doctors who are fully responsible for the safety monitoring of the devices. However, although C.R. Bard knew about the device fracturing loosening, and migration issues as early as 2004, the company decided not to report their concerns to the FDA. Instead, they asked Dr. John Lehmann to determine if newer models showed a reduced rate of failure. The internal document was meant to be secret, however, it was accidentally disclosed suggesting a possible manufacturer negligence in warning the public of known risks.

Article by Dr. Claudio Butticè, PharmD.

REFERENCES

- Young T, Tang H, Hughes R (2010). Young, Tim, ed. “Vena caval filters for the prevention of pulmonary embolism”. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD006212. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006212.pub4. PMID 20166079.

- Goldhaber SZ (2005). “Pulmonary thromboembolism”. In Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS; et al. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine (16th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. pp. 1561–65. ISBN 0-07-139140-1.

- Food and Drug Administration. “Inferior Vena Cava (IVC) Filters: initial Communication: Risk of Adverse Events with Long Term Usage”. United States Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2015-03-15.

- Sarosiek S, Crowther M, Sloan JM. “Indications, complications, and management of inferior vena cava filters: the experience in 952 patients at an academic hospital with a level I trauma center.” JAMA Intern Med. 2013 Apr 8;173(7):513-7. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.343.

- Nicholson W, Nicholson WJ, Tolerico P, Taylor B, Solomon S, Schryver T, McCullum K, Goldberg H, Mills J, Schuler B, Shears L, Siddoway L, Agarwal N, Tuohy C. “Prevalence of fracture and fragment embolization of Bard retrievable vena cava filters and clinical implications including cardiac perforation and tamponade.”Arch Intern Med. 2010 Nov 8;170(20):1827-31. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.316. Epub 2010 Aug 9.

- Tam MD, Spain J, Lieber M, Geisinger M, Sands MJ, Wang W. “Fracture and distant migration of the Bard Recovery filter: a retrospective review of 363 implantations for potentially life-threatening complications.” J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012 Feb;23(2):199-205.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.10.017. Epub 2011 Dec 20.

Be the first to comment on "IVC Filters – a life-threatening medical device"